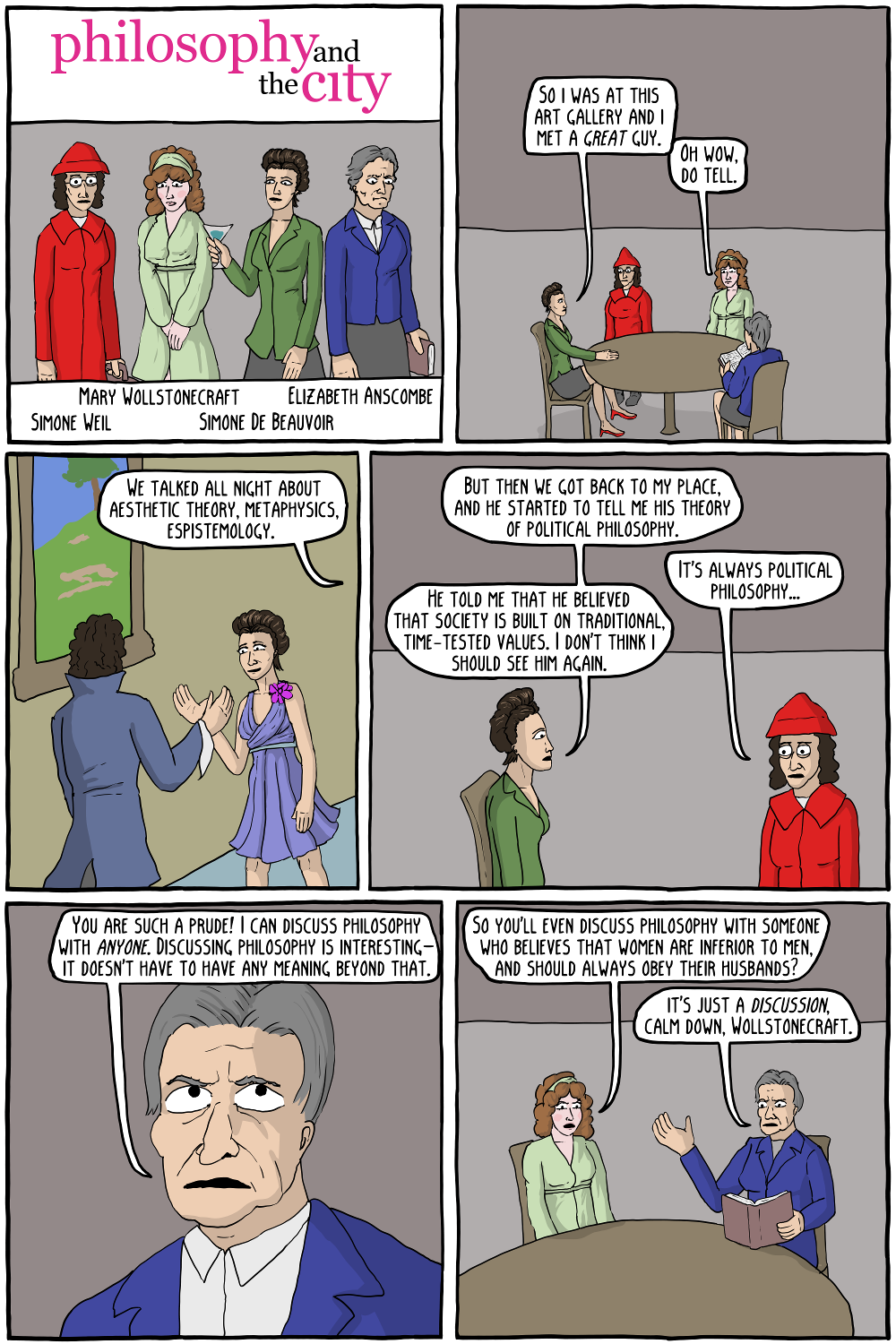

Simone de Beauvoir was very critical of philosophy and other intellectual pursuits that become totally detached from the world. She claimed that intellectuals cannot in good faith be "a-political", and merely pursue intellectual aims. Everyone is part of the world, so must in some sense take an ethical stance. Failing to act isn't a merely passive existence, but is also a kind of action, for Beauvoir. This was particularly pressing for Beauvoir, as she lived in a time of great social upheaval, as well as the German occupation of France in World War II. Many intellectuals preferred to "not get involved", in France and elsewhere.

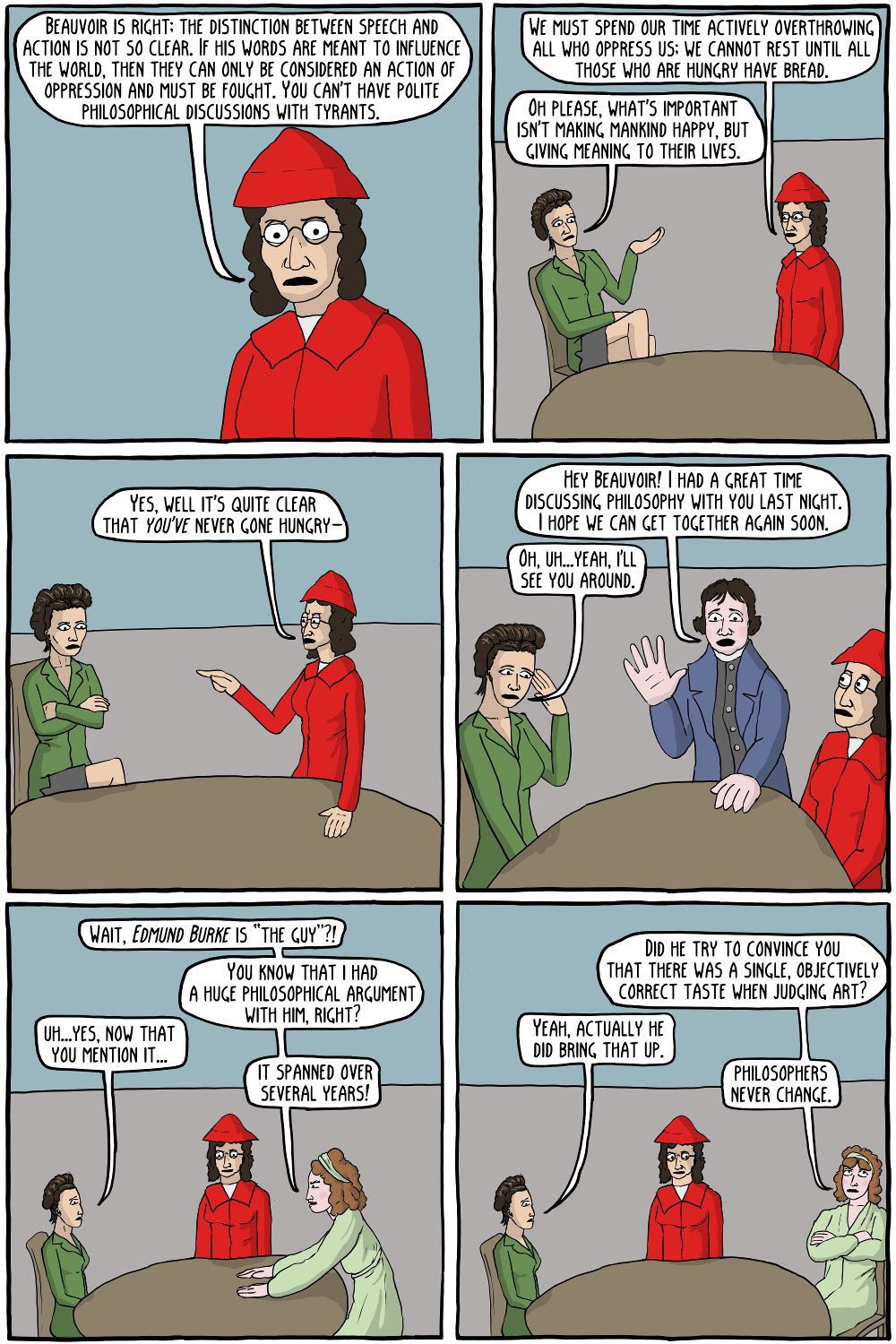

Simone Weil was a contemporary and classmate of Beauvoir's. Beauvoir greatly admired her for her incredible commitment to action (as did Camus, who called her the only great spirit of the age). Simone Weil was a great activist for socialism, and even joined in the Spanish Civil War, despite her rather frail and sickly constitution, and natural clumsiness (she burnt herself on a cooking fire, and had to be sent home). The exchange with Beauvoir is reproduced almost verbatim from Simone de Beauvoir's journal. To quote from this article on Weil:

Simone de Beauvoir recounts her one meeting with Weil during their university days. De Beauvoir recounts that already at that time Weil had established a somewhat intimidating reputation. Coming upon Weil in a courtyard of the Sorbonne while Weil was holding forth on the need for revolution in order to feed the masses, de Beauvoir recalls that her own offering to the conversation was the philosopher's opinion that what the people really needed was meaning in their lives. Weil frostily replied, quickly looking her over, that it was clear that she had not ever gone hungry, a remark that de Beauvoir recognized as putting her and her philosophy in its place as belonging to the petty bourgeoisie.

In The Need for Roots, Weil examines the idea of "free speech", claiming that most intellectuals of the time had it wrong. While she believed that individuals should have "absolute freedom of speech", she did not believe that this covered institutions, or the freedom to blatantly disregard facts. So for example, if a newspaper prints propaganda for Fascism, the State can revoke it, because the newspaper doesn't have free speech, only the individuals (obviously this would be a thorny thing to work out the details of). Individuals can hold fascist opinions, and discuss them, but the government has no obligation to protect the rights of groups, which don't properly exist (so in other words, she thought freedom of the press should be more limited, but not freedom of speech). Furthermore, even an individual could be guilty of a crime if they are spreading lies, she gives the example of an author who claimed that there was no serious consideration in Ancient Greece that slavery was wrong. However she points out that Aristotle, who was pretty much the only one to comment on slavery at all (defending it), gives this line: 'Some people assert that slavery is absolutely contrary to nature and reason.' A curious thing to say if all were in agreement on the issue of slavery. She says the author should be brought before a court to explain himself, and if he can't, he would be guilty of a crime (although we can assume that he would be spared from the gulag, in this particular case.)

The In Our Time podcast has a good episode on Weil, detailing her rather crazy life, and her thinking.

Mary Wollstonecraft was a philosopher and early feminist. Her most famous works are A Vindication of the Rights of Men, a criticism of Edmund Burke's defense of constitutional monarchy, and his attack on the French Revolution; and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, one of the earliest feminist works, arguing, well...that women should have rights. Like I said, this was pretty early in feminism, although she also has some pretty advanced critiques of Burke's essays on beauty, accusing him of using language to relegating beauty to the realm of the feminine, which is weak and emotional by nature.

Elizabeth Anscombe was a philosopher and logician in the 20th century. She wasn't as politically active as the other three women, as well as being more conservative. She worked mostly on logic, philosophy of language, and ethics.

Edmund Burke was a 18th century philosopher, statesmen, and political theorist. He is best known for being a founding thinker in modern conservatism. He attacked the French Revolution for trying to build an entire society a purely ideological basic, disregarding the tried and true foundations that have kept society running for hundreds of years (i.e., he believed in slow reform rather than revolution). A lot of what he warned against ended up coming true in the case of the French Revolution, which turned in to a bit of a disaster. He defended a lot of institutions that the later socialists (such as Beauvoir and Weil) were trying to dismantle, such as the classes, private property, and the aristocracy.

The comic is a parody of Sex and the City.

Permanent Link to this Comic: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/116

Support the comic on Patreon!